Antiracist art of Elizabeth Catlett: from the masses, to the masses

Thursday, December 31, 2020 at 1:13PM

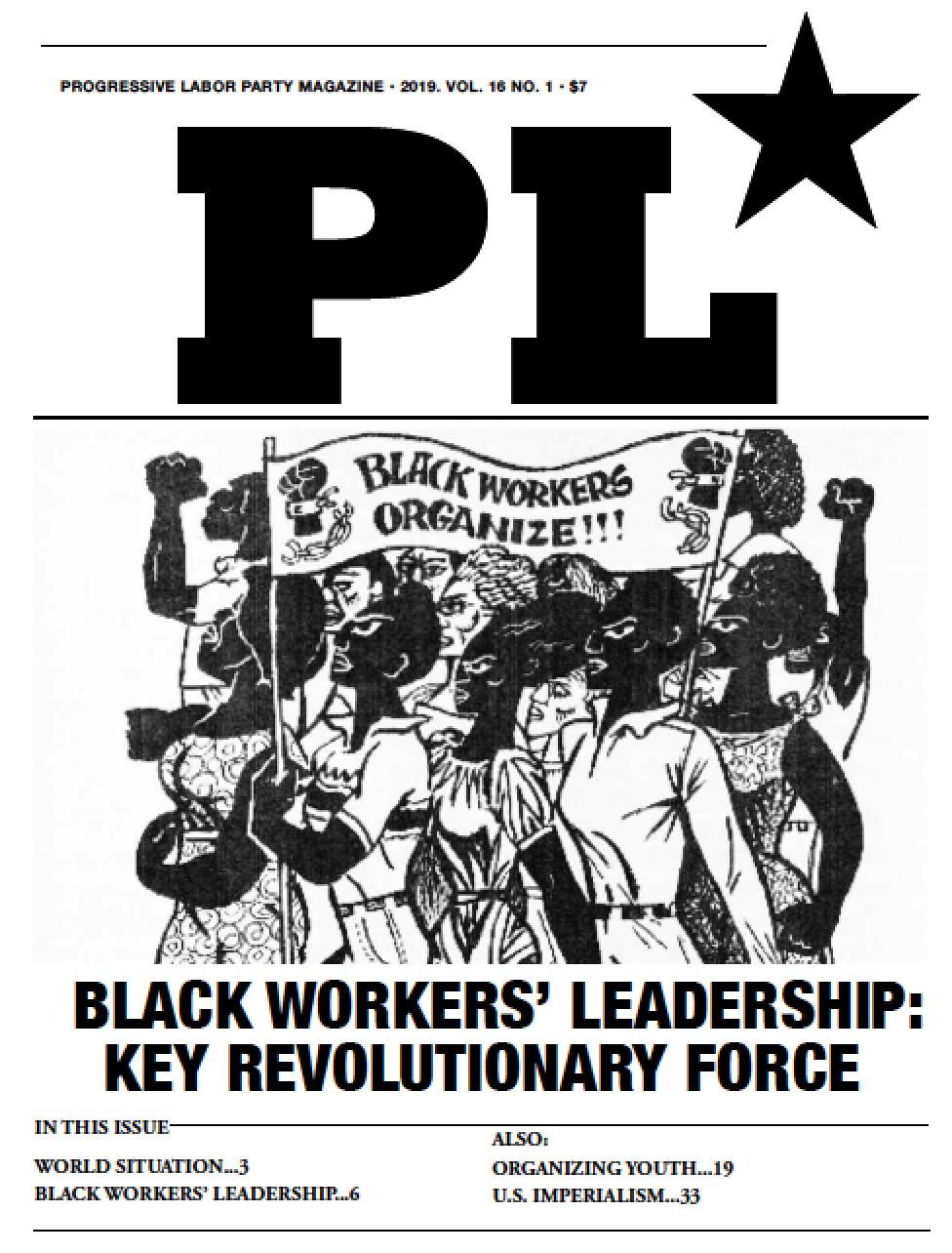

Thursday, December 31, 2020 at 1:13PM Elizabeth Catlett, a Black artist and teacher, drew inspiration from the working-class struggles of her family and neighbors and from the long history of multiracial struggles for civil rights and egalitarianism. She urged all Black artists to contribute to the fight against racism through their subject matter, to shun segregated exhibitions, and to make art that would reach a broad audience. In a 1961 speech to the National Congress of Negro Artists in Washington, D.C., in the spirt of the communist principle, “from the masses, to the masses,” Catlett said: “If we are to reach the mass of Negro people with our art, we must learn from them; then let us seek inspiration in the Negro people – a principal and never-ending source.”

Catlett’s own art consisted of semi-abstract figural sculptures, large and small, and prints, either linotypes or lithographs. Her sculptures, carved from wood or stone or cast in bronze, deemphasize details to indicate monumental heads, powerful bodies, and, on occasion, clenched fists. In one moving political work, Homage to My Young Black Sisters (1968), a female figure lifts her head and raises her fist in the international gesture of solidarity. Some of Catlett’s large sculpture pieces can be found in public spaces, like Olmec Bather at the National Polytechnical Institute in Mexico City or People of Atlanta in Atlanta’s City Hall.

In her prints, Catlett created powerful images of Black people and also workers in Mexico, where she lived for many years. Sharecropper (1970) depicts a white-haired Black woman with strongly chiseled features and a straw hat, looking up and over her shoulder. The color linotype Malcolm X Speaks for Us (1969) reflects Catlett’s identification with the civil rights struggles of the times. Other subjects include Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Thurgood Marshall, Frederick Douglass, and Phillis Wheatley, the African-born poet who was enslaved in Boston and died in poverty at the age of 31.

A Passionate Teacher

Catlett was born in Washington in 1915, in the heart of Jim Crow racism, the daughter of a public school teacher and a truant officer. Her father died before she was born. Catlett planned to attend the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh for an art degree, but her scholarship was revoked when the administration discovered she was Black. She wound up studying design and painting at Howard, the historically Black university, with financial help from her mother until a scholarship came through. After earning her Masters of Fine Arts at the University of Iowa, she taught briefly at a college in Texas and then directed the art department at Dillard University, the leading Black college in New Orleans. Teaching would be her lifelong passion.

In 1941, the year she married fellow artist Charles White, Catlett’s career took off with a first prize at the American Negro Exposition for her sculpture, Mother and Child. The couple moved to New York, where Catlett studied with Ossip Zadkine, a Russian-born French émigré, who urged her to adopt a more modernist, simplified style, and to approach art from a “humanistic international viewpoint.”

Later she explained that her approach was to begin with her personal experiences in the U.S. and then “be projected towards international understanding, as our blues and spirituals do. They are our experience[s], but they are understood and felt everywhere” (Romare Bearden and Henry Henderson, A History of African American Artists from 1792 to the Present, 1993).

After a teaching stint at Hampton Institute in Virginia, Catlett made a political leap upon returning to New York, where she joined the George Washington Carver School, a left-leaning community art center, run on a shoestring, that filled the vacuum after the government’s Works Progress Administration (WPA) art centers folded in the early 1940s.

For two years she taught sculpture and dressmaking. Like so many organizations fighting racist segregation in that era, the Washington Carver School folded under pressure from anti-communists. But working with the poor, proud, and struggling people of Harlem made a lasting impression on Catlett.

Collectivity and Struggle in Mexico

In 1946, Catlett and White moved to Mexico, where she embarked on “Negro Women,” a series of 15 linocuts. She took up printmaking with the Taller de Gráfica Popular, a collective of communist and progressive artists, and studied the work of the great Mexican muralists: Diego Rivera, David Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco. After divorcing White, Catlett married painter and printmaker Francisco Mora and settled into life in Mexico. She raised three sons and thrived in working collectively with other artists. As she’d recall, “I learned that art is not something that people learn to do individually, that who does it is not important, but its use and its effects on people are what is most important.” Later Catlett joined the faculty of the Escuela Nacionale de Bellas Artes, Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico (UNAM), where she became head of the sculpture department until her retirement in 1976.

Always attuned to workers’ struggles, Catlett moved within communist artistic and literary circles in Mexico City. In 1949, as she later told a member of Progressive Labor Party, she joined with striking railroad workers and their communist supporters. Subsequently she found herself harassed by the Mexican government, which hunted U.S. expatriates considered by the F.B.I. to be “subversives.” One night, when one of her sons was ill and her husband was out giving a concert, Mexican officials barged into her home and took her in for questioning. She spent two nights in detention before her release.

After Catlett became a Mexican citizen in the early 1960s, the U.S. government refused to issue her a visa to re-enter the U.S., a ban that wasn’t lifted until 1971, for her major exhibition at the Studio Museum in Harlem. Nevertheless, she was a continued presence in the U.S. through her art, her participation in exhibitions, and her large following. Through her death in 2012, in Cuernavaca, Mexico, Catlett never faltered in her opposition to segregation, her fightback against racism, and her championing of working-class women and men.

Progressive Labor Party (PLP) fights to destroy capitalism and the dictatorship of the capitalist class. We organize workers, soldiers and youth into a revolutionary movement for communism.

Progressive Labor Party (PLP) fights to destroy capitalism and the dictatorship of the capitalist class. We organize workers, soldiers and youth into a revolutionary movement for communism.

Reader Comments